Image Credits: Image generated by DALL-E.

Table of contents

- Introducing infrastructure as code (IaC)

- Introduction to Terraform

- How does Terraform work?

- Conclusion

Introducing infrastructure as code (IaC)

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) refers to the process of managing and provisioning infrastructure using code rather than manual processes. When we talk about “infrastructure as code,” we mean that we manage our IT infrastructure with code in the form of configuration files.

Configuration files that describe our infrastructure are produced by IaC. Changes and sharing of configurations are made simpler as a result. An IaC process produces the same environment every time it deploys, just as the same source code always generates the same binary.

It’s a version control

Version control is an important aspect of IaC, and our configuration files, like any other software source code file, can be under source control.

The difficulty of manually managing infrastructure

Managing IT infrastructure was traditionally a manual process where the deployment team would physically install and configure servers. Unsurprisingly, this manual process would frequently result in several issues.

Uses “declarative” definition files

IaC uses declarative definition files, which are simply configuration files. It’s worth noting that in the declarative approach, we only specify the “what” but not the “how” in our definition files. A definition file specifies the parts and settings required by an environment, but it does not always specify how to obtain those settings. For example, the definition file may specify the required server version and configuration but not the process for installing and configuring the server—we specify the “what” part but not the “how” part.

Benefits of infrastructure as code

Because IaC is text-based, we can easily edit, copy, version, and distribute it.

Speed

The first major benefit of IaC is its speed. We can quickly set up your entire infrastructure by running a script with infrastructure as code. That is something we can do for any environment, from development to production.

Consistency with reduced errors

Manual processes are prone to errors. Infrastructure as a code solves this problem by making the configuration files the single source of truth. That way, we can be certain that the same configurations will be deployed repeatedly and without error.

Traceability with the help of a version control system

We have full traceability of the changes made to each configuration because we can version IaC configuration files like any other source code file, which allows us to save time troubleshooting the problem.

Introduction to Terraform

Terraform is an open-source infrastructure as a code tool from HashiCorp. It enables us to define both cloud and on-premises resources in human-readable declarative definition files (aka configuration files) that can be versioned, reused, and shared. These definition files contain the steps required to provision and maintain our infrastructure. We can edit, review, and version these definition files just like code.

Terraform can create infrastructure on a variety of cloud platforms such as AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, etc.

Download and install

Terraform distribution consists of a single binary file, which can be obtained for free from Hashicorp’s download page. There are no dependencies, so we can just copy the executable binary to a folder of our choice and run it from there. HashiCorp also offers a managed solution known as Terraform Cloud.

After we finish the installation, we can run the following command to ensure that everything is working properly:

$ terraform -v

Terraform v1.2.7

on darwin_amd64

Terraform core concepts

Below are the core Terraform concepts:

Blocks

Blocks are containers for other content, and they typically represent the configuration of an object, such as a resource. The block body is delimited by the { and } characters.

Blocks have:

- A block type

- Zero or more labels

- A body that contains any number of arguments and nested blocks. Top-level blocks in a configuration file control the majority of Terraform’s features.

Block syntax

This is the Terraform block syntax:

<BLOCK TYPE> "<BLOCK NAME>" "<BLOCK LABEL>" {

# Block body

<IDENTIFIER> = <EXPRESSION> # Argument

}

These are some of the Terraform blocks:

- providers

- resources

- variable

- output

- local

- module

- data

Block example

resource "aws_instance" "demo" {

ami = "ami-1fc93908a9403"

network_interface {

# ...

}

}

In the above example, a block has a type as resource. The resource block type in our case expects two labels: aws_instance and demo.

The Terraform language uses a limited number of top-level block types, which are blocks that can appear outside of any other block in a configuration file. The majority of Terraform’s features, such as resources, input variables, output values, data sources, and so on, are implemented as top-level blocks.

Providers

Terraform makes use of providers to connect the Terraform engine to the supported cloud platform. Other than a cloud platform, other things can be considered a provider, such as platform-as-a-service (PaaS) (e.g., Kubernetes) and other software-as-a-service (SaaS).

It’s a Terraform plugin that serves as a translation layer, allowing Terraform to communicate with a variety of cloud providers, databases, and services.

Terraform’s most popular providers, including major cloud providers:

- AWS

- Azure

- Google Cloud Platform

- Kubernetes

- Oracle Cloud Infrastructure

Each provider adds a set of resource types and/or data sources that Terraform can manage. Every resource type is implemented by a provider; Terraform cannot manage any infrastructure without providers.

Where do providers come from?

The Terraform Registry is the primary directory of publicly available Terraform providers, hosting providers for the majority of major infrastructure platforms.

Provider syntax

The general syntax is as follows:

resource "<PROVIDER>_<TYPE>" "<NAME>" {

[CONFIG...]

}

The PROVIDER above is the name of the provider (e.g., aws). The TYPE is the type of resource to create in that provider (e.g., instance, which represents an EC2 instance). The NAME is the identifier we can use throughout the Terraform code to refer to this resource. The CONFIG consists of one or more arguments that are specific to that resource (e.g., ami = “ami-1fc93908a9403”).

For instance, the aws_instance resource has many different arguments, but for now, we only need to set the following:

ami: The Amazon Machine Image (AMI) to run on the EC2 instance.instance_type: The type of EC2 Instance that will be used. Each EC2 Instance type has a different amount of CPU, memory, disk space, and networking capacity. We uset2.microinstance. T2 instances are available to use in the AWS Free Tier, which includes 750 hours of Linux and Windowst2.microinstances each month for one year for new AWS customers.

An example of a simple configuration is as follows:

resource "aws_instance" "demo" {

ami = "ami-1fc93908a9403"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

}

Variables and outputs

Variables in Terraform are an excellent way to define centrally managed, reusable values. Information contained in Terraform variables is stored independently of deployment plans. Terraform supports multiple variable formats. Based on their usage, the variables are generally divided into:

- Input variables - They serve as parameters for a Terraform module, allowing users to modify behavior without having to edit the source code.

- Output values - They serve as return values for a Terraform module.

- Local values - They are a convenience feature for assigning a short name to an expression.

Modules

Modules are small, reusable Terraform configurations that allow us to manage a collection of related resources as if they were one. A module serves as a container for multiple resources that are used together. To put it simply, a module is a set of Terraform configuration files (.tf files) in a single directory as shown below:

.

├── main.tf

├── outputes.tf

└── variables.tf

Even a single Terraform configuration file (.tf) in a directory becomes a module. When Terraform commands are executed directly from such a directory, the contents of that directory are considered the root module.

Having said that, a module is a method for packaging and reusing configurations of resources.

What does a module do?

A module enables us to group related resources together and reuse them in the future, multiple times.

Let’s assume we need to repeatedly create a virtual machine with a set of resources such as IP, firewall, storage, etc. This is where modules come in handy; we don’t want to repeatedly write the same configuration code over and over again.

The below example demonstrates how our “server” module may be invoked. Here, we create two instances of “server” using a single set of configurations:

module "server" {

count = 2

source = "./module/server"

...

...

}

State

Terraform must keep track of what infrastructure it creates in a terraform.tfstate Terraform state file-local state stored on the provisioning machine. Terraform uses this state to map real-world resources to our configuration. Terraform state is stored locally by default, but it can also be stored remotely, which is preferable in a team environment.

This state file contains a custom JSON format that records a mapping from the Terraform resources in our templates to their real-world representation.

Avoid directly manipulating the state file! The state file is meant only for internal use within Terraform. This implies that we should never manually edit the Terraform state files or write code that directly reads them. If for some reason we need to manipulate the state file, use the

terraform importorterraform statecommands.

Terraform makes use of this local state to create plans and modify our infrastructure. Terraform performs a refresh prior to any operation to update the state with the real infrastructure.

Remote state

When working with Terraform in a team, using a local file complicates Terraform usage because each user must ensure that they always have the most recent state data before running Terraform and that no one else runs Terraform at the same time.

A remote state comes to our aid. Terraform writes the state data to a remote data store, which can then be shared by all team members.

Terraform can store state in a variety of storage platforms, including, but not limited to:

- Terraform Cloud

- HashiCorp Consul

- Amazon S3

- Azure Blob Storage

- Google Cloud Storage

- Alibaba Cloud OSS

Remote state is implemented by a backend or by Terraform Cloud, both of which can be configured in the root module of our configuration.

Data sources

Terraform can use data sources to get information about resources that are set up outside of Terraform and use that information to set up Terraform resources. It’s a way of getting data from the outside world and making it available to your Terraform configuration.

A data source is accessed through a special type of resource called a data resource, which is declared using a data block.

Data source example

data "azurerm_role_definition" "example" {

name = "Developer"

}

resource "azurerm_role_assignment" "example" {

role_definition_id = data.azurerm_role_definition.example.id

}

In the above example, we have defined two blocks: data and resource blocks. We are sending the data from the data source directly into a role assignment resource.

Refreshing data sources

By default, before creating a plan, Terraform will refresh all data sources. Additionally, we can explicitly refresh all data sources by executing terraform refresh command.

Resources

The most important element of the Terraform language is resources. Each resource block describes one or more infrastructure objects, such as virtual networks, compute instances, and so on.

Resource syntax

resource "aws_instance" "web" {

ami = "ami-a1b2c3d4"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

}

In the above example, a resource block declares a resource of a given type (aws_instance) with a given local name (web). The name is used to refer to this resource from within the same Terraform module, but it has no significance outside of the module. The combination of the resource type and name serves as an identifier for a given resource and must therefore be unique within a module.

Command line interface

We can use the Terraform command line interface (CLI) to manage infrastructure, and interact with Terraform state, providers, configuration files, and Terraform Cloud.

Terraform CLI commands

Following shows some of the Terraform CLIs:

terraform versionterraform init [option]- This command is used to initialize a working directory containing Terraform configuration files and install the required plugin.

Policy libraries

A library of policies that can be used within Terraform Cloud to accelerate our adoption of policy as code.

HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL)

The HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL) is a one-of-a-kind configuration language created by HashiCorp. HCL was created to work with HashiCorp tools, specifically Terraform. The Terraform language’s primary function is to declare resources, which represent infrastructure artifacts.

Configuration syntax

HCL is intended to support multiple syntaxes for configuration, but the native syntax is the primary format and is optimized for human authoring and maintenance rather than machine generation. The native configuration syntax of HCL is relatively easy for humans to read and write.

The file extension of the configuration file written in HCL syntax is .tf. The Terraform language also allows us to define resource dependencies. A configuration can consist of multiple files and directories.

Declarative configuration

As previously stated, this configuration language is declarative, which means that we only describe the infrastructure we want, and Terraform will figure out how to build it. In other words, it means that we describe our intended goals (what to be done) rather than the steps (how to be done) to achieve those goals.

The configuration files we write in the Terraform configuration language tell Terraform:

- What plugins to install?

- What infrastructure to create?

- What data to fetch?

Basic configuration elements

The syntax of the Terraform language consists of only a few basic elements:

- Blocks

- Arguments

- Expressions

Blocks

Refer above for more details.

Arguments

Arguments assign a value to a name. They can be found within blocks.

image_id = "abc123"

The identifier before the equals sign is the argument name (image_id in our case), and the expression after the equals sign is the argument’s value (abc123 in our case).

Expressions

Expressions represent a value in one of two ways: directly or by referencing and combining other values.

CDK for Terraform (CDKTF)

The Cloud Development Kit for Terraform (CDKTF) enables us to define and provision infrastructure using familiar programming languages. You might wonder why we need CDKTF when HCL can do the same thing. As mentioned above, CDKTF enables us to define and provision infrastructure using familiar programming languages other than HCL or JSON syntax.

At the time of writing this post, Terraform supports the following programming languages:

- Typescript

- Python

- Java

- C#

- Go

CDKTF uses the Cloud Development Kit from AWS, which provides a set of language-native frameworks for defining infrastructure, as well as adapters that allow underlying provisioning tools to use those definitions.

Install CDKTF

We can install CDKTF with npm on most operating systems. We can also install CDKTF with Homebrew on MacOS.

Install CDKTF with npm

To install the most recent stable release of CDKTF, use npm install with the @latest tag as shown below:

npm install --global cdktf-cli@latest

Install CDKTF using Homebrew

We can also use the Homebrew package manager to install CDKTF on MacOS systems.

brew install cdktf

Verify the CDKTF installation

Verify that you have CDKTF installed by running the cdktf help command to show the available subcommands.

How does CDK for Terraform work?

On a high level, we will follow these steps:

-

Step 1 - Define infrastructure: As a first step, define the infrastructure we want to provision on one or more providers using any of the supported programming languages. CDKTF works by translating configurations defined in an imperative programming language to JSON configuration files for Terraform.

-

Step 2 - Deploy: Use

cdktfCLI commands to provision infrastructure with Terraform or synthesize (translate to other form) our code into a JSON configuration file that others can use with Terraform directly.

CDKTF to HCL

The cdktf synth command synthesizes (generate code/configuration) Terraform configuration for the given app. CDKTF stores the synthesized configuration in the cdktf.out directory, unless you use the --output flag to specify a different location.

The output folder is ephemeral (short lived) and might be erased for each synth that we run manually or that happens automatically when we run deploy, diff, or destroy.

HCL to CDKTF

Use the cdktf convert command to translate Terraform configuration written in HCL to the equivalent configuration in our preferred language.

Convert a local file:

cat main.tf | cdktf convert > imported.ts

CDKTF CLI commands

The following are some of the CDKTF CLI commands:

cdktf version

How does Terraform work?

As stated above, Terraform uses definition files to create and manage resources on cloud or on-premises platforms, as well as other services via their APIs. Terraform’s primary function is to create, modify, and destroy infrastructure resources as described in a Terraform configuration.

Definition or configuration files

Terraform requires infrastructure configuration or definition files written in either HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL) or JSON syntax.

Working directories

Terraform expects to be invoked from a working directory containing Terraform language configuration files. Terraform uses configuration content from this working directory to store settings, cached plugins and modules, and occasionally state data.

Working directory contents

A Terraform working directory typically contains:

- A Terraform configuration (

.tffiles) that defines the resources that Terraform should manage. This configuration is likely to change over time. - A hidden

.terraformdirectory, which Terraform uses to manage cached provider plugins and modules, record which workspace is currently active, and record the last known backend configuration in case it needs to migrate state on the next run. This directory is automatically managed by Terraform, and is created during initialization. - State data, if the configuration uses the default

localbackend. This is managed by Terraform in aterraform.tfstatefile (if the directory only uses the default workspace) or aterraform.tfstate.ddirectory (if the directory uses multiple workspaces).

The following shows all the files in a working directory, including the hidden ones:

$ tree -a

├── .terraform

│ └── providers

│ └── registry.terraform.io

│ └── hashicorp

│ └── local

│ └── 1.4.0

│ └── darwin_amd64

│ └── terraform-provider-local_v1.4.0_x4

├── .terraform.lock.hcl

├── hello.txt

├── main.tf

└── terraform.tfstate

Provisioning infrastructure with Terraform

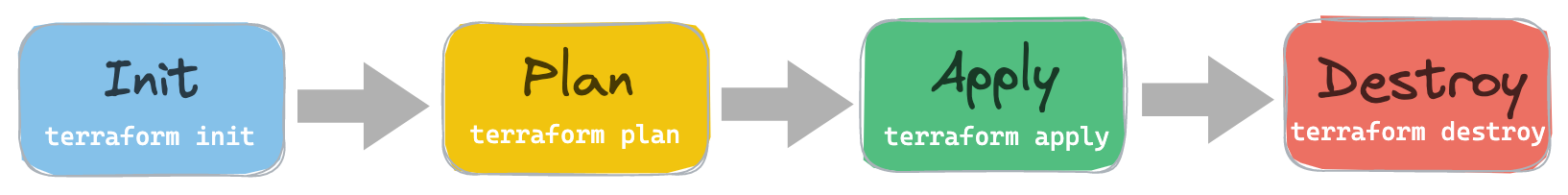

The provisioning workflow (Terraform’s life cycle) in Terraform is based on the following commands:

initplanapplydestroy

Figure 1: Terraform life cycle.

Init

Init command initializes the working directories. A working directory must be initialized before Terraform can perform any operations on it, such as provisioning infrastructure or changing state.

Why do we need to initialize the working directory, and what happens during initialization? The terraform binary contains the basic functionality of Terraform, but it does not include the code for any of the providers (e.g., the AWS provider, Azure provider, GCP provider, and so on), so when we first start using Terraform, we must run the terraform init command to instruct Terraform to scan the code (configuration file), determine which providers we are using, and download the code from the Terraform Registry. The provider code is downloaded by default into a .terraform directory.

Note: It’s safe to run init multiple times because the command is idempotent.

After initialization, we will be able to perform other commands, like terraform plan and terraform apply.

Plan

After we’ve initialized the working directory, we’ll use the plan command to see what actions Terraform will take to create our resources. This step works similar to the “dry run” feature found in other build systems. This is an excellent way to double-check our changes before releasing them.

The plan command’s output is similar to the diff command’s output:

- Resources with a plus sign (

+) will be created. - Resources with a minus sign (

-) will be deleted. - Resources with a tilde sign (

~) will be modified in-place.

$ terraform plan

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# local_file.hello will be created

+ resource "local_file" "hello" {

+ content = "Hello, Terraform"

+ directory_permission = "0777"

+ file_permission = "0777"

+ filename = "hello.txt"

+ id = (known after apply)

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

Terraform’s plan output indicates that it needs to create a new resource, which is expected given that it does not yet exist. We can also see the provided values that we’ve specified, as well as a pair of permission attributes. Because we did not include them in our resource definition, the provider will use the default values.

Apply

We can now use the apply command to create actual resources:

$ terraform apply

Terraform used the selected providers to generate the following execution plan. Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# local_file.hello will be created

+ resource "local_file" "hello" {

+ content = "Hello, Terraform"

+ directory_permission = "0777"

+ file_permission = "0777"

+ filename = "hello.txt"

+ id = (known after apply)

}

Plan: 1 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

╷

│ Warning: Version constraints inside provider configuration blocks are deprecated

│

│ on main.tf line 2, in provider "local":

│ 2: version = "~> 1.4"

│

│ Terraform 0.13 and earlier allowed provider version constraints inside the provider configuration block, but that is now deprecated and

│ will be removed in a future version of Terraform. To silence this warning, move the provider version constraint into the

│ required_providers block.

╵

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value: yes

local_file.hello: Creating...

local_file.hello: Creation complete after 0s [id=392b5481eae4ab2178340f62b752297f72695d57]

Apply complete! Resources: 1 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

We can now confirm that the file was created with the desired content:

$ cat hello.txt

Hello, Terraform

Also, after running terraform apply, the terraform.tfstate file has been created with the following content:

$ cat terraform.tfstate

{

"version": 4,

"terraform_version": "1.2.7",

"serial": 1,

"lineage": "bd8530c6-6781-a52a-2c26-dd1164afc7cd",

"outputs": {},

"resources": [

{

"mode": "managed",

"type": "local_file",

"name": "hello",

"provider": "provider[\"registry.terraform.io/hashicorp/local\"]",

"instances": [

{

"schema_version": 0,

"attributes": {

"content": "Hello, Terraform",

"content_base64": null,

"directory_permission": "0777",

"file_permission": "0777",

"filename": "hello.txt",

"id": "392b5481eae4ab2178340f62b752297f72695d57",

"sensitive_content": null

},

"sensitive_attributes": [],

"private": "bnVsbA=="

}

]

}

]

}

Destroy

When we’re finished experimenting with Terraform, we should delete all of the resources we created so the cloud service provider doesn’t charge us for them.

Cleanup is simple because Terraform keeps track of what resources we created. All we have to do is execute the destroy command.

$ terraform destroy

When we type “yes” and press enter, Terraform will create the dependency graph and delete all the resources in the correct order, using as much parallelism as possible.

Terraform in action

In this section, let’s perform a series of exercises.

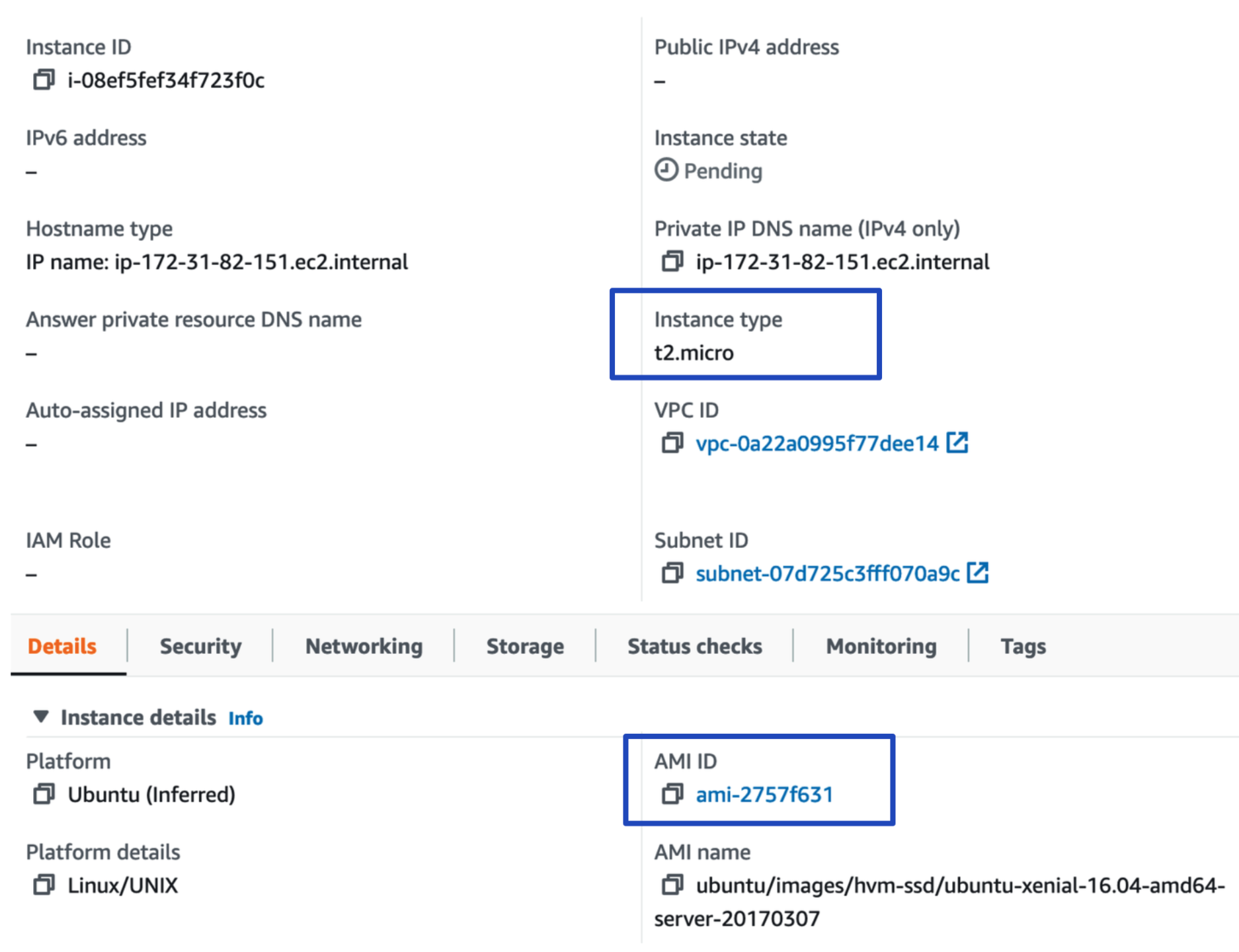

Exercise #1 - Create an AWS EC2 instance

Create a Terraform configuration file with the content as shown below and save it in the main.tf file:

provider "aws" {

profile = "default"

region = "us-east-1"

}

resource "aws_instance" "example" {

ami = "ami-2757f631"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

}

The above definition file uses two blocks: provider followed by resource blocks.

In the provider block, we use AWS as our cloud provider and the default AWS profile, which indicates the use of the default credentials (ACCESS KEY ID and SECRET ACCESS KEY) from the /.aws/credentials file.

In the resource block, the AWS resource (resource type) to be created has been specified. In this example, we specified aws_instance, which represents the EC2 instance. Also, we specified additional parameters such as ami and instance_type that might be required for the creation of an EC2 instance.

The following steps will be performed in order to create an EC2 instance:

- Step 1: Initialize the working directory by executing the command

terraform init. - Step 2: (Optional) Validate the configuration file (

main.tf) by executing the commandterraform validate. - Step 3: Perform a dry run to see what changes occur when the command

terraform planis executed. - Step 4: Execute Terraform by running the command

terraform apply. This is the actual execution step where Terraform, after successfully authenticating, creates an EC2 instance. - Step 5: (Optional) Destroys the instance we created in the above step by executing the command

terraform destroy -target aws_instance.example.

Note: As previously mentioned, Terraform keeps track of the infrastructure it creates in a state file called

terraform.tfstate, which is stored locally on the provisioning machine by default. This state file is generated during the execution of Terraform, i.e., when theapplycommand is executed.

Once Terraform has been successfully executed, a new EC2 instance is created in our AWS account as shown below:

Figure 2: New EC2 instance created in AWS.

As shown in the screenshot, an EC2 instance was created with the given instance type t2.mirco and the AMI ID specified in our definition file.

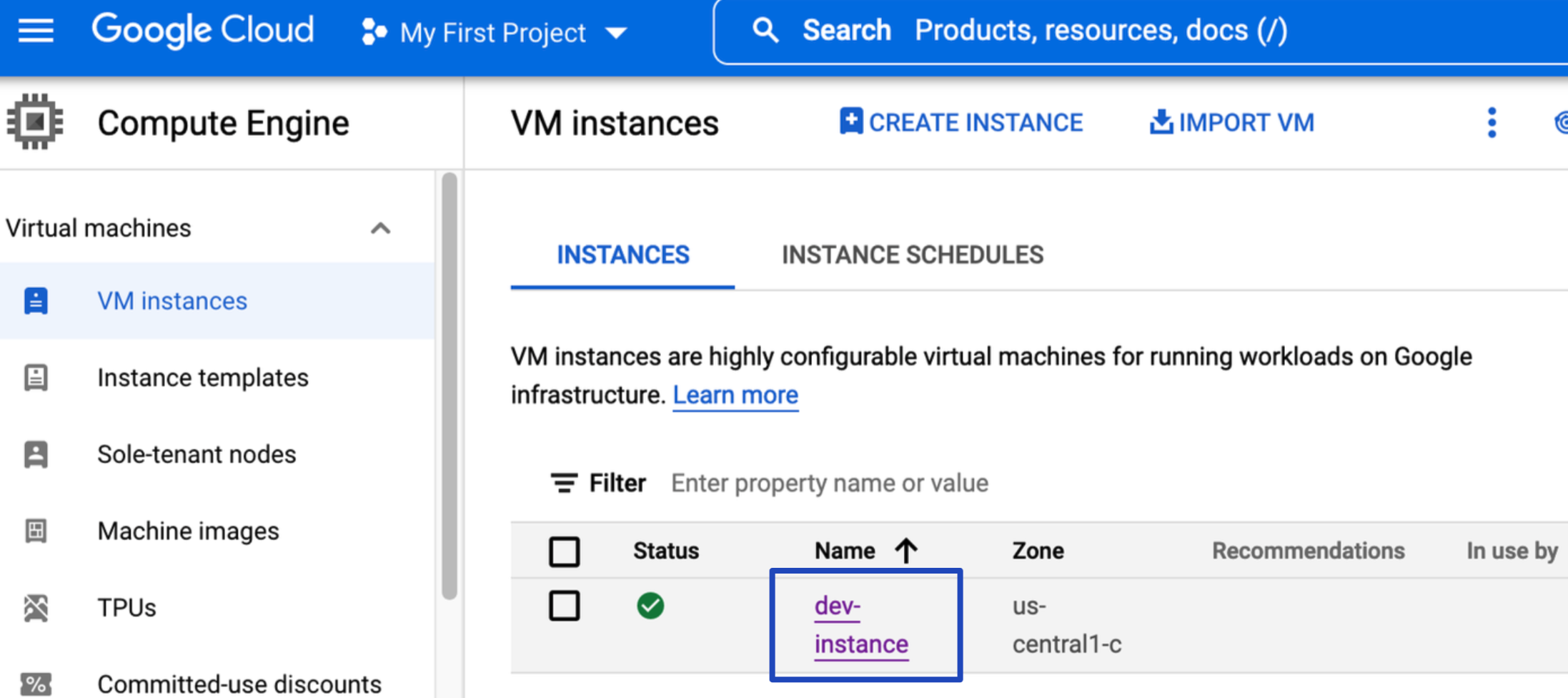

Exercise #2 - Create a compute engine in GCP

In this exercise, a compute engine instance will be created.

Pre-requisites

- GCP account

gcloudCLI must be installed.- Ensure we have a IAM service account with role as Owner. To verify, use the following command to list the service-accounts:

gcloud iam service-accounts list - Create a key for the service account so that Terraform can connect to GCP using this key. Use the following command for the same:

gcloud iam service-accounts keys create google-key.json --iam-account <service account email id>. This would create a new key file namedgoogle-key.jsonin the current directory. We can also generate key via Google Cloud web console. - We must enable Compute Engine API by visiting the Google Cloud console’s Compute Engine page.

Create a Terraform configuration file with the content as shown below and save it in the main.tf file:

provider "google" {

credentials = file("proud-sweep-359704-f460da53c31e.json")

project = "proud-sweep-359704"

region = "us-central1"

zone = "us-central1-c"

}

resource "google_compute_network" "vpc_network" {

name = "demo-network"

}

resource "google_compute_instance" "dev_instance" {

name = "dev-instance"

machine_type = "f1-micro"

zone = "us-central1-c"

boot_disk {

initialize_params {

image = "centos-cloud/centos-7"

}

}

network_interface {

network = "default" // This enable private IP address

access_config { // This enable private IP address

}

}

}

To create a Compute Engine instance (it’s a VM) in GCP, the following steps will be performed:

- Step 1:

terraform init. - Step 2: (Optional)

terraform validate. - Step 3:

terraform plan. - Step 4:

terraform apply. - Step 5: (Optional)

terraform destroy -target google_compute_instance.dev_instance.

Once Terraform has been successfully executed, a new Google Compute Engine (GCE) instance is created in our GCP account as shown below:

Figure 3: A new GCE instance created in GCP.

Conclusion

This should help you understand the fundamentals of Terraform and how infrastructure as code can be set up quickly and efficiently. The declarative language simplifies the process of describing the infrastructure we intend to build, as opposed to describing how to build it. Before putting our changes into action, we use the plan command to test them and look for potential bugs.

This is merely a summary of how efficiently infrastructure as code can be implemented with Terraform. I attempted to make this post as clear as possible while still providing sufficient detail for you to understand the ideas. For more details, check out their online documentation.

Comments